What makes a great public sector leader in 2023, and how do National Health Service leaders measure up? As the NHS marks its 75th anniversary amid soaring waiting lists, strikes over pay, and staff shortages, the country needs reassurance we are in safe hands. The NHS Long Term Workforce Plan published last month sets out an ambitious strategy, but how ready are those leaders in charge of our NHS provider organisations to take these plans forward?

In this article, Alison Sortwell, Senior Consultant, Health and Leadership & Talent Consultancy, shares GatenbySanderson’s research findings, to present the typical profile of current NHS leaders. Alison compares this to other areas within the Public Sector including Local Government, to explore how future-ready our NHS leaders are, highlighting their key strengths and challenges.

As the NHS marks its 75th anniversary amid soaring waiting lists, strikes over pay, and staff shortages, strong leadership has never been more important, as highlighted by the Messenger Review (2022). The publication of the NHS Long Term Workforce Plan (June 2023) sets out an ambitious strategy to address workforce challenges. Against this backdrop, GatenbySanderson has explored the capability of current leaders of NHS provider organisations, specifically looking at their style, traits and behaviours to understand what makes a great NHS leader.

We answer questions such as:

- What are the approaches which may be contributing to success?

- What are the risk areas that could be hindering success?

Then, comparing against leaders in other areas of the Public Sector, we explore similarities and differences:

- How future-ready are current leaders?

- What strengths might they need to leverage?

- What areas might need developing?

- What gaps need filling, to navigate the challenges of our post-pandemic environment?

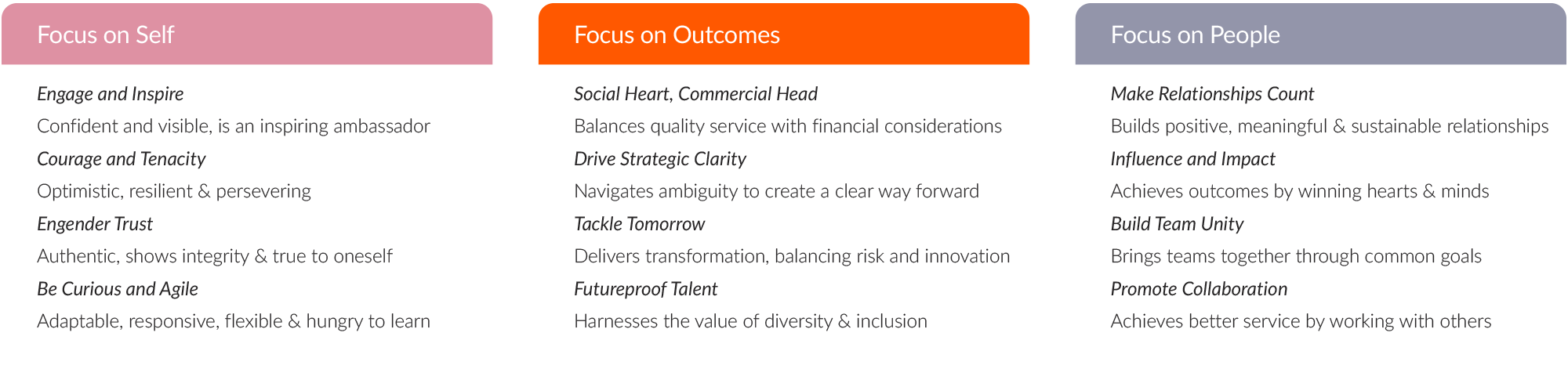

We’ve answered these questions using data against our GatenbySanderson leadership model, Altitude, which is the only model to benchmark behavioural excellence for leaders working across the Public Sector.

The Altitude Model

The Altitude model consists of 12 behaviours falling into three clusters; Focus on Self, Focus on Outcomes and Focus on People. Assessment data, for over 5,000 leaders, has been mapped to these behaviours giving us a benchmark to compare leader capability in Health against the broader Public Sector.

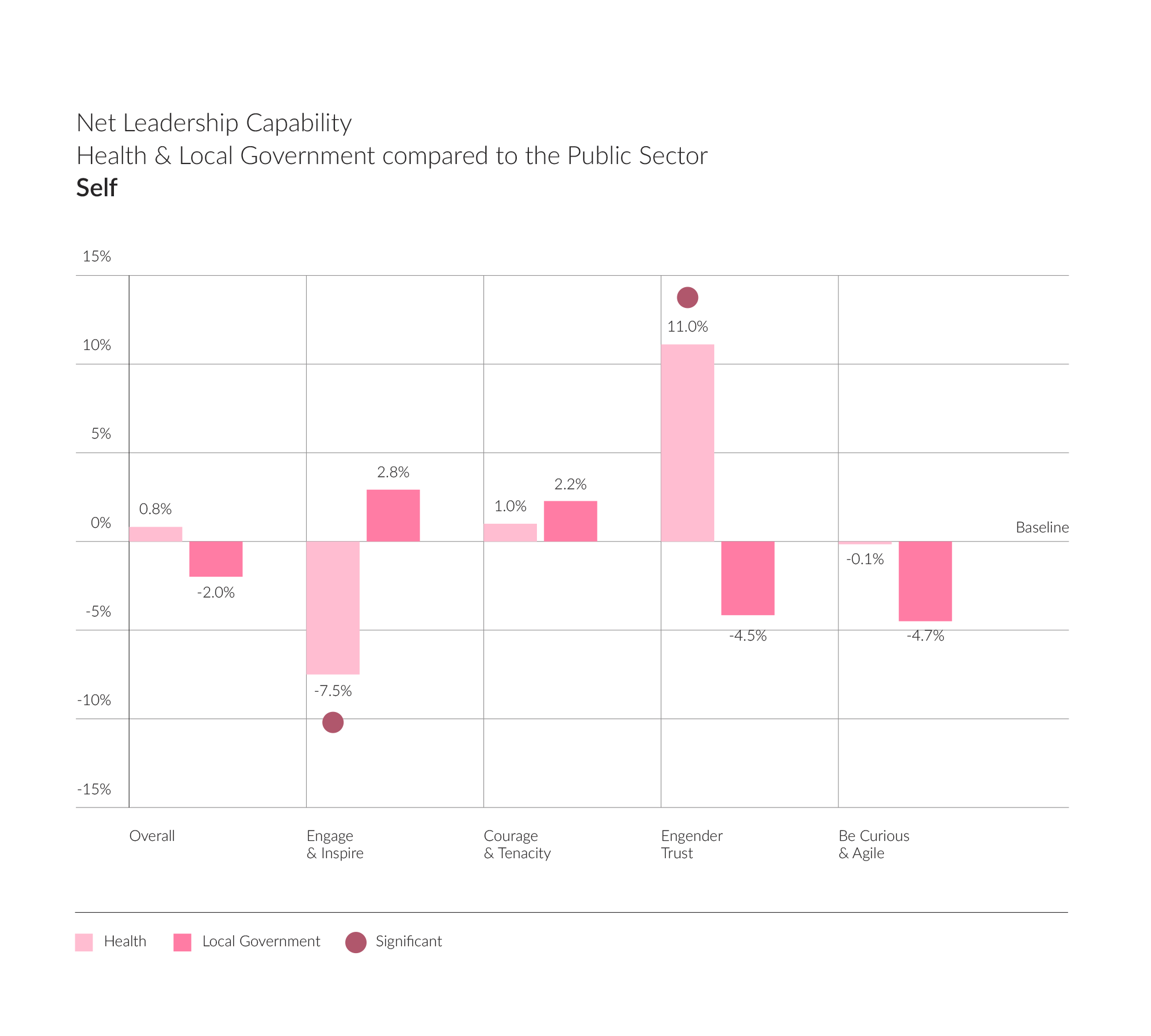

Our data for nearly 1,000 leaders in NHS provider organisations has been benchmarked against the wider Public Sector (over 5,000 leaders). We explore the variance in relation to the 12 core behaviours of the GS Altitude model.

From this data, we can see trends where NHS leaders differ from other areas in the Public Sector. We highlight the areas where there is a statistically significant difference and discuss the potential reasons behind these differences. Where Health leaders show behaviours that are greater than the baseline, we refer to these as strengths, and where they fall below the baseline, we will refer to risks.

We not only compare the trends in the NHS to the public sector as a whole; we also specifically look at similarities and differences with Local Government, since parallels are strong – especially since the introduction of the Integrated Care System and the focus on social care.

Might leaders in health be able to learn from their counterparts in local authorities?

Furthermore, in an environment where appointments tend to be made from within, we explore the case for bringing in greater diversity of leadership backgrounds from other areas across the public and even the public sectors, to tackle some of the challenges the NHS is facing.

We also take into consideration the findings from the landmark health and social care Messenger Review (2022), which involved extensive stakeholder engagement, identifying “institutional inadequacy” in leadership and management across the Health and Care sectors, in the way that leaders are trained, developed and valued. The report made 7 recommendations for recovery These are addressed through the eagerly awaited NHS Long Term Workforce Plan (2023), which NHS leaders will play a key part in putting into action, especially around the area of embedding the right culture and improving retention, by improving culture, leadership and wellbeing.

Furthermore, the NHS Long Term Workforce Plan references Our Leadership Way – which sets out the compassionate and inclusive behaviours the NHS want to see in all leaders and how they interact with employees (we are Compassionate, we are Curious, we are Collaborative) – has a focus on values-led approaches. We have mapped this model to our Altitude model and make reference to these approaches in this article.

We explore themes in line with the 3 focus areas of the GS Altitude model.

- Focus on Self. Here we will look at the shift from the heroic leader to compassionate leader; how successful this shift has been and what the potential impact might be.

- Focus on People. Here we look at system leadership and collaboration, to explore how the ICB structure may have resulted in a shift in style, the effectiveness of partnership working, and what strengths and risks we are seeing linked to this structure.

- Focus on Outcomes. While the patient is at the heart of all NHS work, many external factors are taking the blame for the current challenges. What control do leaders have over the outcomes and deliverables needed by the NHS?

Theme 1: A positive shift towards Compassionate Leadership

Engenders Trust – which is about being authentic, showing integrity and being true to oneself – is a clear strength for NHS leaders compared to the Public Sector baseline. We see a significant difference here. This is perhaps not unsurprising when we consider the reasons leaders follow a career path with the NHS (patient focussed, care, integrity). Furthermore, we are seeing a greater focus on Values for NHS provider organisations, guiding recruitment decisions and organisational behaviours. NHS Trusts want their leaders’ style to be aligned with their Trust’s values. Language such as openness and transparency appear often. This strength also seems to be consistent with the shift towards ‘compassionate leadership’ in healthcare. NHS England defines compassionate leaders as having: “values and behaviours that inspire understanding and trust, build inclusion and reduce inequalities”. Our findings support this, suggesting that building trust is a strength for NHS leaders. This is a positive and encouraging finding for the sector in the current climate.

On the other hand, our data tells us that Engage and Inspire is a risk area for NHS leaders compared to the Public Sector baseline. If we look at the descriptors of this competency, we may start to understand why NHS leaders have shifted away from this style of leadership. In the GS Altitude model, this competency is about being confident and visible, and an inspiring ambassador. First, if we consider visibility, this became a practical challenge during the pandemic. While front-line work continued, many ‘office’ roles became remote and leaders themselves needed to reduce their interactions. NHS leaders have had to adapt to become visible in new ways, using different channels of communication. While technology has helped here, has there been a sufficient return to ‘walking the floor’ and visibility?

Second, GS’s definition of Engage and Inspire paints the image of a leader who is inspiring, highly self-confident, with strong presence, commanding credibility and respect, inspiring people through their passion – many of the traits of the ‘heroic leader’. We know that the NHS has tried to move away from this style of leadership in favour of the ‘compassionate leader’. If we explore Michael West’s explanation of Compassionate leadership, we see that it is more about having impact by carefully listening to, understanding, empathising with and supporting other people. It is about making people feel valued. Our findings suggest that the shift to compassionate leadership for the NHS may be more than an aspiration and is beginning to materialise.

Furthermore, the NHS Long Term Workforce Plan highlights the importance of compassionate leadership: “Collective, inclusive, and compassionate leadership is increasingly recognised as essential for delivering high quality care and cultural change throughout the NHS. Our Leadership Way, and the recommendations of […] Kark and Messenger reviews, describe the management capabilities and compassionate and inclusive behaviours leaders need to give staff the backing they require to deliver for patients”.

This approach will play great importance in supporting greater inclusion and diversity in the NHS, particularly around supporting the pipeline of future leaders from more diverse backgrounds.

By contrast, our findings suggest that leaders in Local Government show a risk in the area of Engendering Trust, falling below the baseline for the public sector overall. This suggests that Health may be placing greater emphasis compared to local authorities on transparency, trust, and values-led leadership. Conversely, Local Government show greater strength in the area of Engaging and Inspiring suggesting that they may still be displaying a more traditional ‘heroic leadership style’.

Theme 2: A need for greater Influence and Impact from partnership working

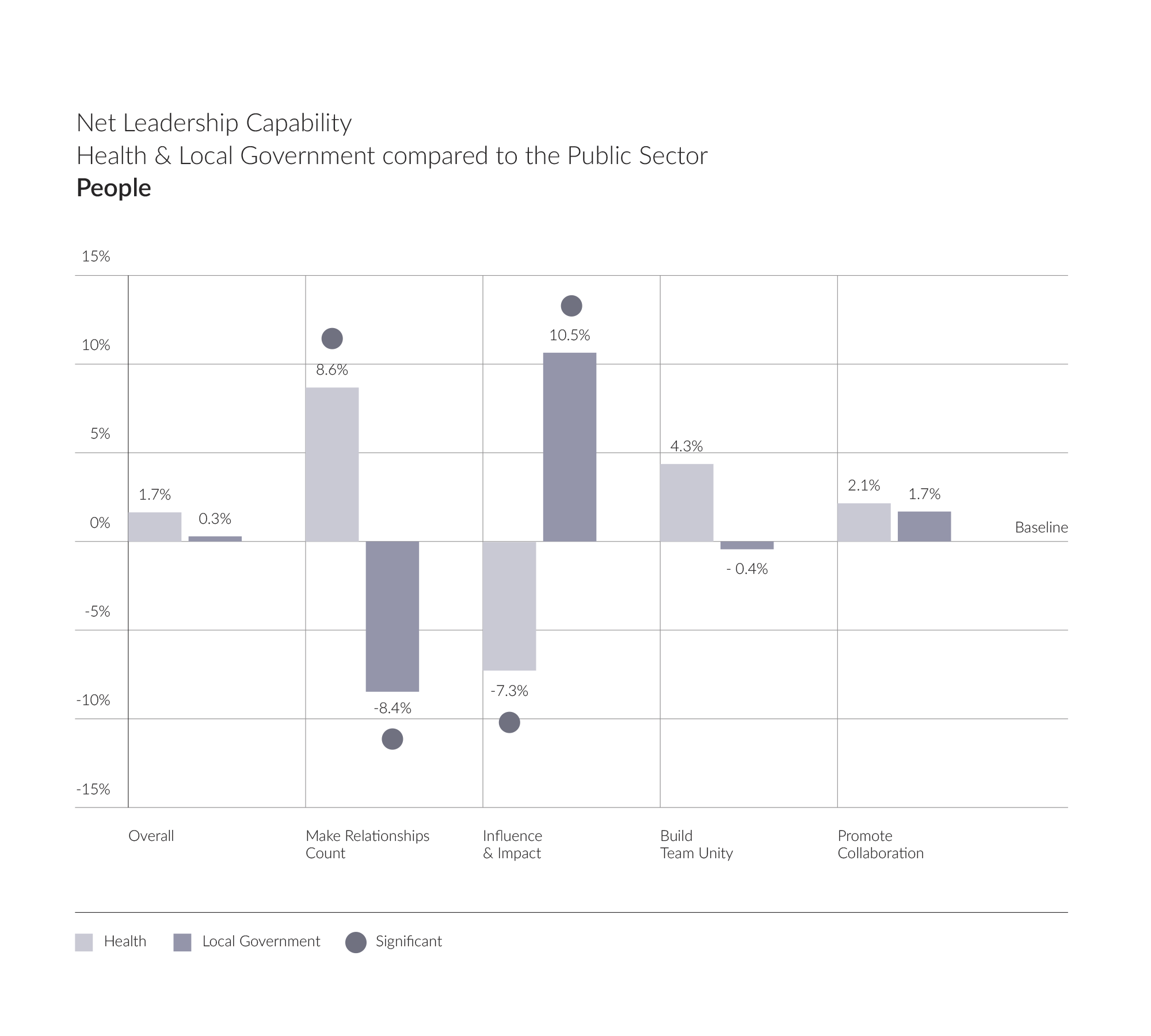

Making Relationships Count – which is about building positive, meaningful and sustainable relationships – is a clear strength for NHS leaders compared to the public sector baseline. We see a significant difference here. What does this tell us? NHS leaders appear to be investing energy in forging strong relationships and building their networks. The data suggests that this is happening internally (Building Team Unity) and externally (Promoting Collaboration), although not to the extent that gives us statistically significant evidence on those specific activities.

While NHS leaders appear to have the right foundations in place to support collaborative working, we can see from the graph that Influence and Impact – which is concerned with winning hearts and minds and being politically astute, is a risk area for NHS leaders. In an environment where partnership working and system leadership is key, the ability to effectively influence others to reach joint outcomes is imperative. Might these findings suggest a gap for NHS leaders? While many external factors are at play, the success of the recent changes which have introduced the new Integrated Care Board structure hinges on effective system leadership and the ability to influence others, getting multiple stakeholders on board to achieve joint outcomes.

So what are these findings telling us? NHS leaders appear to be placing emphasis on building strong relationships, connecting and working together, but are they yielding results? Might they be placing too much energy into setting up connections but losing sight of what they need to achieve from these relationships?

If we look at the profile across Local Government leaders in this area, we see the opposite pattern: a gap for Making Relationships Count, and a strength for Influence and Impact (compared to the public sector baseline). What is this style telling us and how should we interpret these contrasting findings? It suggests that local government leaders are investing less time in people, yet they are having greater success in winning people over. Could it be greater political influence? It may be down to a perception of a lack of control over outcomes for NHS leaders.

The results suggest that in order to have a greater impact and achieve better results from the new structures, NHS leaders may need greater clarity over the outcomes they are seeking to influence. This is a possible development area for NHS leaders, and potentially an area where outside perspective and experience could benefit the sector.

Theme 3: A need for greater focus on outcomes

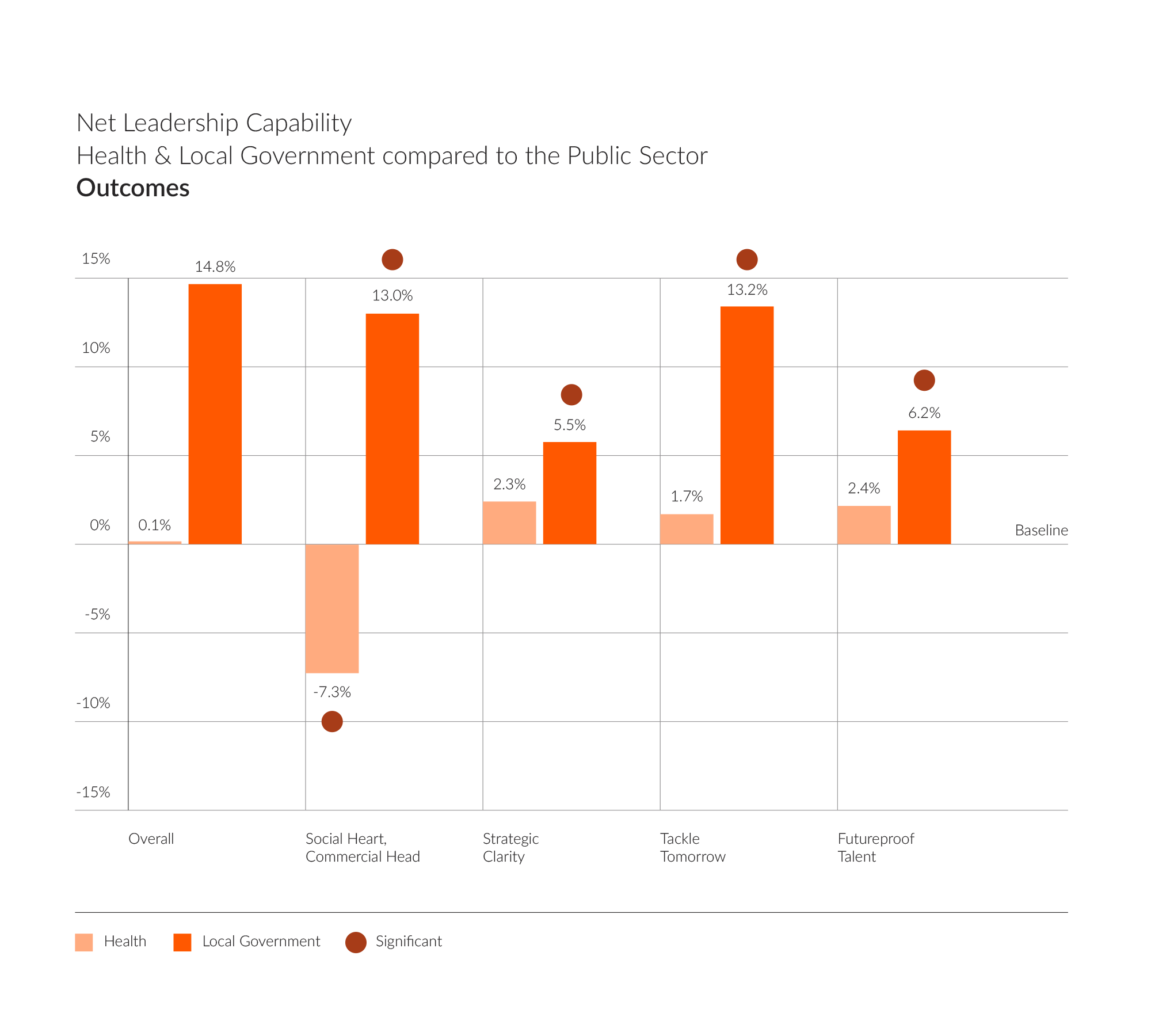

Overall, the trends for this area are fairly disappointing for NHS leaders. While they are reasonably aligned with the rest of the public sector around strategy, change, and future planning, these areas are not significant strengths. Considering the scale of challenges faced by the NHS, we would hope to see greater strength in these outcome-focused behaviours from leaders.

Social Heart and Commercial Head, appear to be a risk area for NHS leaders. This is about balancing a quality service with financial considerations. One could argue that this area is outside of NHS leaders’ control. Indeed, data from The Health Foundation (2023) tells us that current growth in health funding falls well below the long-term historical average. We are seeing the lowest investment ever recorded since 1980. The sector is operating at a deficit and is likely to continue to do so. What is the role of NHS leaders in bridging the gap, should they be looking at new ways to tackle these challenges? How can they look at achieving greater efficiencies without compromising patient safety? Can NHS leaders learn here from other sectors?

Indeed, by contrast, leaders of local authorities seem to be outperforming in this area, displaying significant strength across all four behaviours. Particularly around Social Heart and Commercial Head and Tackle Tomorrow. These findings would indicate that local authorities are achieving more tangible results and outcomes. It is true that local authorities have been dealing with the impact of austerity for longer, with significant cuts impacting the way in which they run their services. They have needed to be more forward thinking in their approach rather than dwelling on the setbacks, creating new income generation streams. Today the NHS is experiencing similar challenges to local government, especially in dealing with the post pandemic recovery. This becomes even more pertinent as they partner up to work more holistically under the new ICS structure. Might Local Authority leaders be responding more positively, learning from lessons of the past? Can NHS leaders learn from their strategic response and their approach to change and transformation?

In summary:

- Our research tells us that the profile of NHS leaders has shifted towards Compassionate Leadership, a style that builds trust, is values-led and supportive of inclusion. NHS leaders need to leverage this style to rebuild staff engagement and support diversity and inclusion.

- NHS leaders are focusing on building relationships to support collaborative working and a system approach. However, they are not having impact and influence necessary to yield the joint outcomes that the new structure was set up to achieve. They can potentially learn from local authority leaders who show greater strength in this approach.

- NHS leaders may be placing too great an emphasis on external factors outside of their control, and losing sight of their role in enabling outcomes and effecting change. In contrast, this is an area of strength for local authority leaders. NHS leaders may benefit from taking advantage of the new structure, to apply some of the approaches adopted by local government.

If you would like to find out more about our Altitude model and how our Leadership & Talent Consultancy team can support NHS leaders in developing the skills identified here, please get in touch alison.sortwell@gatenbysanderson.com

If you would like to find out more about our Altitude model and how our Leadership & Talent Consultancy team can support NHS leaders in developing the skills identified here, please get in touch alison.sortwell@gatenbysanderson.com